Armenia and EU Foreign Policies: Navigating the Conflict, Russia’s Role, and Regional Dynamics

Introduction

The protracted conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan concerning the Nagorno-Karabakh region has inflicted widespread suffering, displacements, and significant geopolitical ramifications. Over the years, external actors, prominently Russia and the European Union, have exerted their influence, significantly shaping the trajectory of the conflict. In this commentary, we delve into the multifaceted dimensions of the Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict, examining the roles played by these external actors and exploring the potential for the EU to assume an active role as a peacekeeper. By analysing the regional dynamics, and the ramifications of the war in Ukraine, we aim to shed light on the complexities of the conflict and highlight the prospects for sustainable peace with EU involvement.

This commentary will delve into the implications of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict on the foreign policies of Armenia and Azerbaijan, as well as the role played by external actors, particularly Russia and the EU. It will also examine how the changing dynamics between Russia and the EU, brought about by the conflict in Ukraine, necessitate a greater EU involvement in mitigating risks, safeguarding human rights, and establishing itself as a prominent regional leader. By understanding the multifaceted dimensions of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict and the shifting geopolitical landscape, we can better comprehend the challenges and opportunities that lie ahead in the pursuit of a lasting peace and stability in the region.

Context

The Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict over the Nagorno-Karabakh region has been marked by sporadic incidents and military clashes since 1994, keeping tensions high and the threat of renewed warfare ever-present. In April 2016, a surge of intense fighting served as a prelude to the larger conflict that was to unfold. Then, in September 2020, full-scale war erupted once again, lasting six weeks and inflicting a heavy toll in terms of military and civilian casualties.

However, a glimmer of hope emerged with the ceasefire brokered by Russia on November 10, 2020, which brought a temporary end to the hostilities. The ceasefire did not provide a definitive and lasting peace, and resulted in Azerbaijan reclaiming control over seven adjacent districts and a significant portion of Nagorno-Karabakh itself. Presently, Russian peacekeepers patrol the remaining area, though self-proclaimed local authorities govern it. The conflict’s repercussions have been devastating, with thousands of lives lost and countless individuals wounded on both sides. Moreover, its political and humanitarian consequences continue to reverberate throughout the region.

Armenia insists that Russian peacekeepers should have full control of the Lachin corridor, the only land link between Armenia and the disputed region of Nagorno-Karabakh. Violations of the Moscow-brokered agreements have led to tensions between the States, with Azerbaijan setting up checkpoints along the corridor. Armenia emphasises that only Russia should control the corridor, while Azerbaijan claims the right to safeguard the road due to safety concerns. The situation highlights the importance of maintaining control over vital transportation routes to ensure stability and prevent further escalation.

The conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan in the Nagorno-Karabakh region has witnessed significant parallels with the war in Ukraine, highlighting the challenges posed by Russia’s reduced capacities as both an aggressor in the west and a peacekeeper in the south.[1] The war in Ukraine, with its prolonged and resource-intensive nature, has strained the Russian military and diverted its attention and resources away from other potential conflict zones. As a result, Russia’s ability to exert its influence as a peacekeeper in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict has been significantly hampered, leaving a void in regional stability efforts. This reduced capacity raises questions about Russia’s ability to effectively manage conflicts on multiple fronts, underscoring the need for other actors, such as the European Union, to play a more active role in promoting peace and stability in the Nagorno-Karabakh region.

The recent clashes in 2020 have intensified the need for a resolution, but the situation remains volatile. The conflict has shifted away from Russia’s mediation towards the involvement of Western actors, particularly the EU. The EU’s interest in the region stems from its desire to stabilise the Eastern Neighborhood and promote conflict resolution.

The EU and Russia

The dynamics of power and relations between Russia and the EU have undergone a seismic shift primarily driven by the war in Ukraine. This conflict has not only upended traditional diplomatic norms but has also ushered in a new era characterised by bolder and confrontational approaches.

The EU now views Russia as a major threat to peace and stability in Europe and the wider neighbourhood. Previously, the EU’s relationship with Russia was based on economic and energy interdependence, but now all aspects of the relationship have been securitised. The EU member states have shown unity in imposing comprehensive sanctions on Russia, resulting in a significant decline in economic relations. Germany, in particular, experienced a 34% drop in exports to Russia in the first half of 2022. The EU is decoupling from Russian oil and gas, which has put pressure on Russia’s economic model and pushed the country towards China and Asia.[2]

China and Russia have been strengthening their economic cooperation, with trade reaching record levels. Despite Russia’s strained relations with the West due to sanctions, China has continued to deepen its economic engagement with Russia. Although, even on this front, Europeans might be on the winning end of the bargain. In June 2023, the 11th package of EU economic sanctions, for the first time targeted countries acting as intermediaries and selling Western technology to Russia, thereby [1] deepening the efforts to isolate Moscow. Whilst only three Chinese companies were targeted, due to well Chinese diplomatic efforts and more iffy member states, notably Greece and Hungary[3], these sanctions might be a starting point to reassess Chinese preferential partners in the long term. China’s relationship with the European Union and the West is becoming increasingly important, especially given China’s current economic challenges[2] . Strengthening ties with the EU might become a priority for China, potentially prompting a re-evaluation of its cooperation with Russia.[4]

In his commentary on “A Paradigm Shift: EU-Russia Relations After the War in Ukraine”, Stefan Meister argues that the EU faces three main challenges in dealing with Russia: building a foreign and security policy based on the recognition of Russia as a major threat, integrating the Eastern neighbourhood outside of Russia, and developing a new Russia policy that is tough on the Putin regime while keeping the idea of a post-Putin Russia as part of Europe.[5] The EU must assert itself as a geopolitical actor in the region and actively manage Russia as a global security risk.

Consequently, with Russia’s ability to serve as a peacekeeper in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict significantly diminished, the EU now had an incentive and geopolitical drive to step forward and assume a more prominent role.[6] The invasion in Ukraine has highlighted the importance of the EU taking the lead in reducing risks for the local population, preserving human rights, and asserting itself as a regional leader. With Russia’s diminished credibility as a neutral arbiter, the EU’s involvement becomes crucial in ensuring a sustainable and just resolution to the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict.[7] Russia’s capacity to act as a peacekeeper in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict has significantly diminished, necessitating the EU to step forward and assume a greater role.[8] This presents an opportunity for the EU to demonstrate its commitment to upholding international norms, promoting peace, and addressing the complex challenges posed by regional conflicts.[9]

The Role of Russia and Armenia-Russia Relations

Russia has historically played a significant role in the region, being a key ally and protector of Armenia. The two countries share cultural, historical, and economic ties. Russia maintains a military base in Armenia and supplied the country with weapons and military support. “Despite Russia acting as a leading mediator in the conflict between the two countries, in 2011–20, it accounted for 94% of Armenia’s imports of major arms and 60% of Azerbaijan’s.”[10] Following the Nagorno-Karabakh war in 2020, a prevailing belief emerged that the West was distancing itself from the region, while Russia held military and political dominance, exerting control over diplomatic proceedings between Armenia and Azerbaijan.However, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has weakened its global standing and raised concerns among its allies, including Armenia.

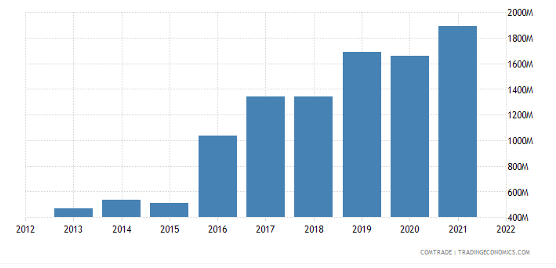

Armenia’s relationship with Russia is complex. On one hand, Armenia relies on Russia for security and is a member of the Moscow-led Collective Security Treaty Organisation. Russia’s military presence in Armenia acts as a deterrent against potential aggression from Azerbaijan. Further, Russia is by far the largest importer of Armenia goods, roughly $789 million in 2021.[11] In 2022, Yerevan was a key instrument for Moscow to keep up the importance of crucial military hardware and bypass certain sanctions imposed by EU partners.[12] While trade with Moscow has almost doubled, much of the growth is attributed to re-exports due to Western sanctions against Moscow. The balance between aligning trade policies to keep up relations with the EU and benefiting from military support and relative security/deterrent from Azerbaijan was certainly complicated to achieve and quite risky in the long run.

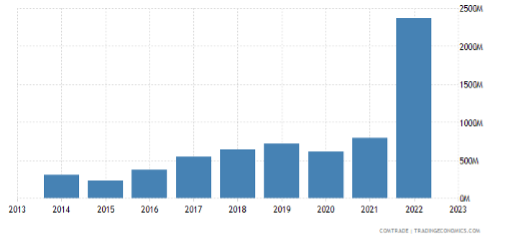

Armenia’s exports to Russia.[13]

Not following EU’s restrictions and becoming complicit in the Russian invasion has massive disadvantages for Armenia. Firstly, this blurs long term relations with the EU, making negotiations for regional investment plans to the disadvantage of Armenia. Second, justifying and unofficially supporting the invasion of a neighbouring territory might be terribly ironic for Armenia, itself constantly on the fence of seeing part of its territory under attack and threats of invasion. Although, precisely for this second point, following EU restrictions might result in decreased Russian military support, putting the country at greater risk.

Russia Exports to Armenia.[14]

On the other hand, Armenia aspires to greater independence and integration with European institutions.[15] It has shown interest in closer cooperation with the EU in the past but, under Russian pressure, joined the Eurasian Economic Union instead. Armenia is dependent on Russia on a number of issues, energy being the most crucial aspect outside of military affairs. The Russian company Rosatom is supervising the only Armenian nuclear power plant’s development until at least 2026 and the state is the sole provider of natural gas, offering preferential tariffs. Further, Russia remains Armenia’s largest trading partner with over 40% FDI in 2021.[16]

Armenia and Russia have transitioned to using only rubles in their mutual trade, abandoning the dollar and euro, as confirmed by Armenian Economy Minister Vahan Kerobyan. The Armenian Central Bank has expressed support for this shift, citing the benefits of eliminating currency fluctuations but acknowledging the associated risks. However, Armenian exporters are significantly impacted by these risks, as the ruble has been volatile and depreciating against the Armenian dram. This situation adds to the challenges faced by exporters, who have already been struggling due to the dram’s appreciation against the dollar. Despite the overall growth in trade between Armenia and Russia, much of it is driven by re-exports rather than domestic production, indicating a disconnect between export volume and actual economic growth in Armenia.[17]

Its economic dependence poses challenges to its efforts to reduce political and security reliance on its longstanding partner and build stronger ties with the West.

Armenia Joining Sanctions against Russia

Armenia’s participation in sanctions against Russia is a complex issue, as it must balance its dependence on Russia for security with its desire to align itself with Western values and interests. While Armenia has taken steps to align with the EU in certain areas, such as signing an agreement on visa facilitation, it has been cautious in joining sanctions against Russia due to its reliance on Russian support in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict.

Armenia is facing scrutiny over its surge in imports of semiconductor chips and electronic components from Europe and America, which are believed to be primarily destined for Russia’s use in military equipment, including missiles involved in the war in Ukraine. Yerevan has seen a significant surge in exports to Russia, with figures showing a 463% increase between 2022 and 2023.[18] The New York Times revealed re-exports rates of certain strategic goods up to 97%. While it cannot deny its involvement, it is attempting to convince the European Union and the United States that its facilitation of Russia’s sanctions evasion should not result in further secondary sanctions.[19] In that spirit, Yerevan committed to working with the EU and the U.S. to block the trade of “risky items” and prevent its businesses from falling on the wrong side of sanctions. Justification implying the duties under the EAEU Treaty will certainly not be enough to avoid long term secondary sanctions, as demonstrated with Belarus and the latest sanction package.

On June 23rd, the European Council adopted the 11th package of sanctions against Russia, extending existing restrictions and adding entities to the sanctions list. This package is specifically aimed at circumventing the loopholes discussed previously and preventing transit of strategic goods through countries trading with the EU. The sanctions list includes 87 new entities, registered in several countries, including Armenia, that are believed to be supporting Russia’s military and industrial complex.[20]

With these new measures, the EU seeks to strengthen monitoring, control, and block re-exports in order to counter Russia’s attempts to evade sanctions. The package also allows for stricter restrictions on the export of sensitive dual-use goods and technology to third countries that could transfer them to Russia.

With the new sanctions targeting the re-exports transiting nations, Armenia will need to rein in the trade of military hardware to prevent its economies from being adversely affected. Although, this can provide an outlet for Armenia, as until the new sanctions, it was forced to balance its economic interests between compliance with international policies and its largest economic partner. Now with new elements tipping the balance towards the EU and US, Armenia might benefit from renewed economic ties and decrease its reliance on Russian imports. But the security issues remain. The conflict with Azerbaijan remains unresolved, and Armenia relies on Russia’s military and diplomatic support to maintain its position in Nagorno-Karabakh. Joining EU sanctions against Russia could jeopardise this support and potentially escalate the conflict.[21]

The precarious situation faced by Armenia is compelling its government to adopt more assertive measures. It must choose between pursuing re-export policies and aligning with Russia to benefit from the peacekeeping protections or opting for the EU route, which entails joining in sanctions but also exposes the country to security risks. In order for Armenia to consider the latter option, the EU will need to offer robust assurances and guarantees.

Armenia and the EU

Armenia’s relationship with the EU has evolved over time. In the early 2010’s, Armenia showed interest in closer cooperation and the possibility of signing an Association Agreement with the EU, which would have included a Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area. This deal would allow Armenia access to the European single market in selected industries and greatly facilitates and encourages EU investments by allowing investors to benefit from the internal EU investment regime, a huge bonus for the country.[22] However, under Russian pressure and faced with the choice of joining the Eurasian Economic Union, Armenia decided to prioritise its relationship with Russia.[23] Nonetheless, the European Union and Armenia have established a Comprehensive and Enhanced Partnership Agreement, which came into force on March 1, 2021. This agreement represents a significant milestone in EU-Armenia relations, as it has been ratified by the Republic of Armenia, all EU Member States, and the European Parliament. The CEPA provides a framework for cooperation between the EU and Armenia in various areas, including strengthening democracy, the rule of law, and human rights, promoting economic growth and job opportunities, improving legislation, public safety, and environmental standards, as well as enhancing education and research opportunities.

The agreement is part of the EU’s broader strategy to deepen and strengthen its relations with countries in the Eastern neighbourhood through the Eastern Partnership framework. High Representative of the European Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy/Vice-President of the European Commission, Josep Borrell, emphasised that the entry into force of the agreement demonstrates the commitment of the EU and Armenia to democratic principles, the rule of law, and a wider reform agenda. He highlighted that the agreement aims to bring positive change to people’s lives and support Armenia’s reform agenda across various sectors, including political, economic, trade, and others.[24]

The CEPA holds the potential to contribute significantly to reducing Russia’s influence on Armenia, particularly by addressing its energy dependence while aligning with the EU’s objective of promoting clean energy access. The CEPA, endorsed by the European Parliament, serves as a framework to strengthen bilateral cooperation and enhance Armenia’s alignment with European standards and norms. By focusing on diversifying Armenia’s energy sources and improving energy efficiency, the agreement can help decrease Armenia’s reliance on Russia for energy imports. Through mainstreaming investments towards clean energy access, the CEPA enables Armenia to tap into renewable energy resources, such as solar, wind, and hydropower, aligning with the EU’s agenda of transitioning to a sustainable and decarbonized energy sector. This shift would not only reduce Armenia’s energy vulnerability but also promote environmental sustainability and support the country’s long-term energy security objectives.

The EU as a Powerbroker

The dispute over the Lachin Corridor, a crucial road connecting Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh, has reignited tensions between the two countries since the end of their previous conflict. The road has been blocked by protesters, causing concerns over potential new hostilities and raising questions about Russia’s role in maintaining security. On the contrary, the EU’s aim to support de-escalation efforts and collaborate closely with both sides towards achieving sustainable peace in the region[25], expressing its support for a peaceful resolution to the conflict, and providing humanitarian aid to the affected populations, is gradually replacing Russia as a primary peacekeeping force in the region.[26]

In the frame of the CSDP, the EU has agreed to launch a civilian mission to Armenia in order to enhance border security and improve relations with Azerbaijan. The mission, requested by Armenia and authorised for a two-year period, will engage in regular patrolling activities along the border to gain a better understanding of the situation on the ground, all the while accelerating diplomatic entente.

The recent meeting between Armenian and Azerbaijani politicians in Brussels, facilitated by European Council President Charles Michel, is the best indication of these progress. Key agreements were reached, including the establishment of transit lines, such as the Zangezur corridor connecting Azerbaijan to its Nakhchivan enclave through Armenian territory.[27] The delineation of boundaries and the formation of an international committee to address the issue were also agreed upon.

By taking a more active role in mediation efforts, while Russia-mediated talks produced no substantial outcomes, the EU is strengthening its diplomatic presence in the South Caucasus. Although Russia still holds considerable influence through its military presence, it is perceived that the Kremlin is not genuinely committed to advancing the peace process, as a resolution would diminish its power and render its troops unnecessary.[28] Consequently, Armenia and Azerbaijan view the EU as a more impartial mediator. It is worth noting the evolving sentiments within Armenia and Azerbaijan. Many in Armenia recognise the need to reach a deal with Azerbaijan, potentially ending two decades of warfare and armed confrontations. A shift in the Armenian government’s rhetoric indicates a change in mindset.[29]

To enhance its influence in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, the EU needs to leverage its economic and diplomatic resources effectively. However, for the EU to become a powerbroker, it must first establish a united and coherent foreign policy approach. The EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy CFSP has been challenged in the past due to diverging national interests among member states.

Whilst the sanction packages are a solid effort toward aligning policies, these are deterrents to collaborate with a third state rather than incentives to meliorate currently frictionious relations. EU foreign policy should prioritise supporting confidence-building measures between Armenia and Azerbaijan, promoting dialogue, and investing in economic development in the region. Additionally, the EU can provide assistance in strengthening democratic institutions and promoting respect for human rights, which would contribute to long-term stability.

Conclusion

The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict poses significant challenges for Armenia’s foreign policy and its relationship with the EU. While Armenia has historically relied on Russia for security, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has shaken the post-Cold War era and raised fundamental questions about European security, creating an opportunity for the EU to increase its engagement in the region. The EU’s rapid agreement on sanctions demonstrates a united response to Russia’s aggression, supported by the cooperation between the EU and the U.S. However, it is crucial for the EU to mobilise its efforts and provide significant support to Ukraine in addressing the humanitarian and economic aftermath of the war. However, the EU must navigate the complex dynamics of the conflict, balance the interests of member states, and work towards a coherent foreign policy approach.

By actively supporting conflict resolution efforts, investing in economic development, and promoting democratic values, the EU can strengthen its influence in the region and contribute to a peaceful and stable resolution of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. This would not only benefit Armenia and Azerbaijan but also advance the EU’s broader goals of promoting peace, stability, and prosperity in its Eastern Neighborhood.

[1] Maximilian Hess. Russia Can’t Protect Its Allies Anymore. Foreign Policy. Available at: https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/09/22/russia-armenia-azerbaijan-war-nagorno-karabakh/

[2] Stefan Meister. A Paradigm Shift: EU-Russia Relations After the War in Ukraine. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Available at : https://carnegieeurope.eu/2022/11/29/paradigm-shift-eu-russia-relations-after-war-in-ukraine-pub-88476

[3] Thomas O’Reilly. EU Sanctions Target China for the First Time. The European Conservative. https://europeanconservative.com/articles/news/eu-sanctions-target-china-for-the-first-time/

[4] ABC News. Beijing downplays Wagner mutiny as experts say China might re-evaluate partnership with Russia. Available at: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-06-27/russian-rebellion-wagner-china-reaction-social-media-diplomacy/102524166

[5] Stefan Meister. A Paradigm Shift: EU-Russia Relations After the War in Ukraine. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Available at : https://carnegieeurope.eu/2022/11/29/paradigm-shift-eu-russia-relations-after-war-in-ukraine-pub-88476

[6] Olesya Vartanyan. The EU’s new role in mediating between Armenia and Azerbaijan. International Politics and Society. Available at: https://www.ips-journal.eu/topics/democracy-and-society/the-eus-new-role-in-mediating-between-armenia-and-azerbaijan-6521/

[7] Kirill Krivosheev. Russian Peacekeepers Find Themselves Sidelined in Nagorno-Karabakh. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Available at: https://carnegieendowment.org/politika/88651

[8] Olesya Vartanyan. The EU’s new role in mediating between Armenia and Azerbaijan. International Politics and Society. Available at: https://www.ips-journal.eu/topics/democracy-and-society/the-eus-new-role-in-mediating-between-armenia-and-azerbaijan-6521/

[10] SIPRI. Arms transfers to conflict zones: The case of Nagorno-Karabakh. Available at: https://www.sipri.org/commentary/topical-backgrounder/2021/arms-transfers-conflict-zones-case-nagorno-karabakh

[11] Observatory of Economic Complexities. Armenia. Available at: https://oec.world/en/profile/country/arm#:~:text=Yearly%20Trade,-%23permalink%20to%20section&text=The%20most%20recent%20exports%20are,%2C%20and%20Bulgaria%20(%24199M).

[12] Armenia: Russia’s backdoor to circumvent sanctions. New Eastern Europe. Available at: https://neweasterneurope.eu/2023/05/26/armenia-russias-backdoor-to-circumvent-sanctions/

[13] Armenia’s exports to Russia. Trading economics. Available at: https://tradingeconomics.com/armenia/exports/russia

[14] Russia Exports to Armenia. Trading Economics. Available at: https://tradingeconomics.com/russia/exports/armenia

[15] Dennis Sammut. Two years after the Velvet Revolution, Armenia needs the EU more than ever. European Policy Centre. Available at: https://www.epc.eu/en/publications/Two-years-after-the-Velvet-Revolution-Armenia-needs-the-EU-more-than~33e910

[16] Marie Lorgeoux. Armenia: what degree of dependence on Russia? Available at: https://regard-est.com/armenia-what-degree-of-dependence-on-russia

[17] Arshaluis Mgdesyan. Eurasianet. As Armenia seeks allies in the West, its economic dependence on Russia grows. Available at: https://eurasianet.org/as-armenia-seeks-allies-in-the-west-its-economic-dependence-on-russia-grows

[18] Russia’s trade partners clamp down on sanctions loopholes in face of EU pressure. Politico. Available at: https://www.politico.eu/article/russia-ukraine-war-vladimir-putin-trade-partners-sanctions-loopholes-in-face-of-eu-pressure/

[19] Russia’s trade partners clamp down on sanctions loopholes in face of EU pressure. Politico. Available at: https://www.politico.eu/article/russia-ukraine-war-vladimir-putin-trade-partners-sanctions-loopholes-in-face-of-eu-pressure/

[20] EU Approves 11th Package Of Russian Sanctions Tightening, Expanding Enforcement. RadioFreeEurope. Available at: https://www.rferl.org/a/eu-russia-sanctions-package-ukraine-war/32472199.html

[21] These economies benefited from Russia’s isolation — but they now risk Western retaliation. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2023/06/07/georgia-armenia-economies-at-risk-over-russia-trade-sanctions.html

[22] EU Commission. EU-Armenia Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/MEMO_13_728

[23] Richard Giragosian. Paradox of power: Russia, Armenia, and Europe after the Velvet Revolution. European COuncil on Foreign Affairs. Available at: https://ecfr.eu/publication/russia_armenia_and_europe_after_the_velvet_revolution/

[24] EEAS. The EU and Armenia Comprehensive and Enhanced Partnership Agreement enters into force. Available at: https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/eu-and-armenia-comprehensive-and-enhanced-partnership-agreement-enters-force_en

[25] EEAS. EU Armenia Mission. https://www.eeas.europa.eu/euma/eu-mission-armenia-euma_en?s=410283

[26] EU greenlights Armenia mission to ease border tensions. Associated Press. Available at: https://apnews.com/article/politics-european-union-azerbaijan-europe-armenia-3f3d9e19dbfe37c8a6aab799b2a3fb59

[27] CEPA. While the Cat’s Away: EU Advances South Caucasus Peace. Available at: https://cepa.org/article/while-the-cats-away-eu-advances-south-caucasus-peace/

[28] CEPA. Armenia — Russia’s Disgruntled Ally. Available at: https://cepa.org/article/armenia-russias-disgruntled-ally/

[29] CEPA. While the Cat’s Away: EU Advances South Caucasus Peace. Available at: https://cepa.org/article/while-the-cats-away-eu-advances-south-caucasus-peace/